Anyone interested in maximizing social good must wrestle with an essential question: given a limited amount of money to contribute to various causes, what is the most effective allocation of those dollars? For whether one is able to donate $100 or $1 billion, the impact of the giving can range from harmful to neutral to transformational. How do we increase the likelihood of the transformational?

This questions drives the Effective Altruism (“EA”) movement, whose adherents seek to do the most good possible in their careers, philanthropy, and other facets of life. One of EA’s philosophical prophets is the ethicist Peter Singer; reading his book, The Life You Can Save, in 2010 significantly influenced my own approach to work and giving. I would distill his argument into the following syllogism: if X dollars can save a life, we are morally obligated to give multiples of X until we reach a level of personal financial discomfort. As a direct result of the book, I have, on average, given away between 20% and 40% of my pre-tax income. (Arguably, not nearly enough.)

The next question is how much does it cost to save a life. A number of economists, sociologists, and others have engaged in fascinating research. Among them is Abhijit Banerjee, who won the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics for his pioneering use of Randomized Control Trials (“RCT”) to evaluate the impact, and cost-effectiveness, of different approaches to social change. This research has spawned organizations like GiveWell, which identify “the charities that save or improve lives the most per dollar.”

For example, GiveWell has found that it costs the Malaria Consortium “about $7 to protect a child from malaria…at an estimated average [cost] of $5,000 per life saved.” In the world of EA, then, the donor might next ask herself: is there a cheaper way to save a life? If not, how much can I afford to give before I significantly reduce my and my family’s quality of life? They might do more research on GiveWell and learn that Hellen Keller International’s vitamin A supplement program can save a life for $3,500. (Of note is that these figures can change, and GiveWell is constantly updating its findings. For example, if an organization receives more money than it can effectively deploy, GiveWell will suggest giving to another org; or the cost per life saved may go up as the org runs out of easy-to-reach people.)

EA has gotten a lot of recent attention, including a New Yorker profile of William MacAskill, another influential thinker in the movement who has just published a book titled What We Owe the Future. But not everyone agrees with EA’s approach, so let’s return the opening question: What is the best way to maximize social good? One criticism of EA is that only giving to direct-service ignores the underlying structures of injustice: rather than strengthening civil society or the economy in a country struggling with malaria, EA focuses on reaching the people underserved by weak institutions. What’s more, if we only give to malaria, vitamin A deficiency, and similar programs, we fail to fund essential research, political and community organizing, and other things that matter to well-being–such as the arts, preserving the natural world, and religious institutions.

To me, the biggest failing, not only of EA but of philanthropically minded people in general (myself included), is our lack of investment in the sphere of policy, organizing, and politics. Consider an issue like child poverty in the United States. Despite our wealth, as of January 2022 17% of children were living at or below the poverty line (for a family of four, the poverty threshold is just $26,500, or $2,200 per month).

There are myriad approaches to addressing this injustice: job-training programs, family- and financial-literacy programs, after-school tutoring, mental-health treatment, and more. Some of these show a modest impact on poverty at the family level, while others demonstrate no impact at all. The cost can also vary wildly–many thousands of dollars per child to, at most, slightly increase a family’s income.

Now consider the impact of public policy. In 2021, when the Democrats enacted into law the American Rescue Plan Act (“ARPA”), they included an expansion of the Child Tax Credit (“CTC”) that was “worth up to $250 per child aged 6 to 17 and up to $300 per child aged under 6, reaching over 61 million children in over 36 million households.” The result? By the end of that year, ARPA “was keeping 3.7 million children from poverty and reducing monthly child poverty by 30 percent.”

Having led a nonprofit for 13 years, I can think of no intervention that would so quickly move the needle. And what made it possible? Simply put, the fact that Democrats had control of the House, Senate, and White House; absent that “trifecta,” the enhanced CTC would not have been brought to life. What’s more, the concept was researched, written about, and promulgated by think tanks like the Center for American Progress. In other words, it was the work of canvassers, political action committees, 501c4 and 501c3 nonprofits, and countless voters, organizers, and others involved in getting Democrats elected, that made this massive reduction in child poverty possible.

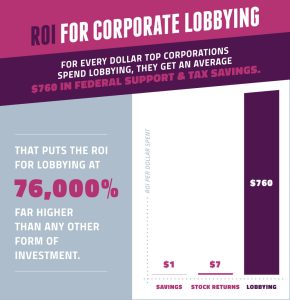

Source: Represent.us

Corporations know the power of political lobbying. One study found that the Return on Investment (“ROI”) on lobbying for top companies if 76,000%. That is, for every dollar spent on lobbying, big businesses “get an average $760 in federal support and tax savings.”

What if we were to achieve that kind of ROI, but in the direction of social and environmental good–and not more corporate profits? This is where EA falls short and where all of us–wealthy and non-wealthy alike–must focus. In the case of the CTC, because of opposition to its extension on the part of Senator Manchin, it was allowed to expire. The solution isn’t for nonprofits to pick up the slack; the solution is for Democrats to maintain control of the House in the 2022 mid-term elections and to expand their control of the Senate. Get that done, and in 2023 the CTC will likely be expanded–provided that activists and voters in general keep up the pressure.

This is not to say that the work of nonprofits, including the one I founded and run, Capital Good Fund, isn’t needed. As a case in point, when the state of Illinois was considering eliminating predatory lending by establishing a 36% APR rate cap on all loans (down from over 500%), legislators would, reasonably, ask if there were alternatives to payday loans and the like. The fact that Capital Good Fund had a fantastic product available to replace those awful loans was repeatedly discussed on the floor of the state house and senate, and helped get the bill over the hump. And beyond that, we need direct-service nonprofits to design and implement programs, plug inevitable gaps in government programs, innovate and experiment with new ideas, and gather input from community members to inform the policy debate.

It’s not, in other words, that political giving is better than direct-servicing giving, or vice versa. Rather, my point is that we have to think about the entire universe of investments that are required in order to build the world we want to see. The political right knows this; groups like the Federalist Society and the Koch Network have spent decades building power at the state level and within the judiciary. The problem, from our vantage point, is that their work has helped the powerful get more powerful. It’s time for people of goodwill to catch up–not only voting for president every four years, but also working to elect good people at every level of government, from the U.S. House and Senate to governorships, state houses, attorneys general, school boards, and more. Additionally, we need to donate to and volunteer / work for groups like Indivisible, Black Voters Matter, Climate Emergency Fund, Run for Something, Center for American Progress, Evergreen Action, Sunrise Movement, Rocky Mountain Institute, Florida Policy Institute, and others that build political power and conduct the crucial research that informs sound public policy.

Leave A Reply