In an increasingly privatized world, it’s worth remembering that some of our most cherished and trusted institutions–NPR, PBS, the USPS, libraries, the Social Security Administration, credit unions–are nonprofit, not-for-profit, quasi-governmental, or governmental entities. And this is true even as trust in a variety of institutions, including Congress, the Supreme Court, and unions, is in decline; one study, in 2020, even found that “Americans have more faith in Google than the government.”

As I write, Elon Musk, much-lauded genius and world-saving entrepreneur, appears to be doing his level-best to precipitate the demise of Twitter, the embattled company with over 200-million users that, while a hotbed of hate and misinformation, also enables countless journalists, activists, authors, elected officials, and government agencies to connect and share information with the public and each other. Writing in The Nation, Nanjala Nyabola has echoed the belief of many, arguing that “Twitter is the closest thing the world has to a transnational public sphere.” Musk, in his rush to save money on his $44 billion investment, doesn’t seem to care; Nyabola notes that “As soon as Musk took over, he fired the human rights team, the Accra-based division of the Africa office, the entire India team, and the engineers who oversaw making the site more accessible to people with disabilities.”

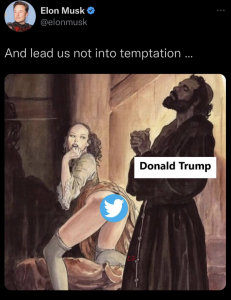

An actual tweet by the wealthiest person in the world

While Twitter may yet survive the fact that, in less than a month, well over half of its staff have been fired or quit and Musk’s childish antics are scaring away the very advertisers without which Twitter has almost no revenue (below is an image of the kind of high-quality, maturity posts he’s been sharing). But whether Musk succeeds in demolishing the company or turning it into a barely-alive zombie, rife with right-wing trolls and hate speech, the public good would be best served by turning Twitter into a trusted, independent nonprofit.

It’s Been Done Before

There is plenty of precedent for how this would work. Below are two useful examples:

National Public Radio (“NPR)” was established under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. Roughly 10% of NPR’s funding comes from the federal government, with the rest derived from charitable contributions and a unique form advertising: NPR doesn’t have commercials but rather “brief statements from major sponsors [that] are called underwriting spots and, unlike commercials, are governed by specific FCC restrictions in addition to truth in advertising laws…” This matters because it reduces the likelihood that, say, fossil fuel companies can launder their reputations through advertising, such as they do on sites like Axios.

Nonprofit journalism has emerged as a response to the worrying decrease in local journalism. Lately, several for-profit newspapers, most notably The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Salt Lake Tribune, have converted to nonprofits. And a whole host of nonprofit journalism outfits, ranging from ProPublica to Mother Jones and thee Center for Investigative Reporting are winning awards and plaudits for their reporting.

How It Could Work

As it did with the establishment of NPR and PBS, Congress could pass legislation that allocates funding to turn Twitter into a nonprofit; or Musk could voluntarily restructure the firm into one. Much more realistically, a donor or group of donors could offer to buy Twitter at a discount with the explicit intention to relinquish control and re-incorporate as a 501c3 tax-exempt organization. Under this approach, Twitter would be governed by an independent Board of Directors that receives no compensation and is represented by a broad array of constituencies, in multiple countries.

Taking away the imperative to generate a profit could allow the nonprofit Twitter to reverse the monetization of attention and outrage that has made the social-media-driven Internet so damaging. Instead, Twitter’s engineers–many of whom would likely flock back to a mission-driven version of the firm–could focus on improving the quality of viral content, reducing hateful content, and fact-checking lies and misinformation. As with NPR, nonprofit Twitter could generate revenue from advertising in a way that doesn’t distort its own work or broader society. And it could raise philanthropic dollars to pilot initiatives that strengthen its ability to drive positive societal outcomes–running randomized control trials on the best way to encourage vaccination, for instance.

While the extent of social-media’s harm to society is a matter of academic and practical debate, there’s no question that bad actors like Putin in Russia or Trump in America have weaponized Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms to drive a hateful agenda. It’s time to short-circuit the extant business model of turning our attention and data into a commodity to be sold to advertisers and influence peddlers. A nonprofit model wouldn’t solve all of its problems–nonprofits struggle with cash flow, divergent opinions and agendas, and all the rest–but it would open the door to a different vision of the Internet, more akin to Wikipedia (which is a nonprofit) than to Facebook, Google, and Amazon. What’s more, Twitter has a 15-year history and hundreds of millions of users to leverage as it embarks on a nonprofit experiment.

Aside from being the center of attention, I can’t see much benefit to Musk pissing away his time and money on a social-media company that is hemorrhaging cash and users, especially when he has at least three other firms to run. So, Mr. Musk, what say you? Why not make Twitter a nonprofit? You can get a big fat tax deduction and extricate yourself from this whole mess, which seems to have started as a joke and, let’s be honest, has become even more of a joke–except, unfortunately, one with real-world consequences.