One could be forgiven for thinking that, with passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, America is all set to reduce emissions and create a bevy of green jobs. In many ways, of course, we are: Climate Power, for instance, has reported that since the bill’s passage, “companies have announced more than 100,000 clean energy jobs in the US.” But greening our economy is going to require more than investments and press releases: we must install terawatts of solar arrays and wind turbines and millions of EV charging stations; triple our electric transmission infrastructure; create new supply chains for batteries and electrolyzers and hydrogen storage; and so much more.

All this construction–steel in the ground, cranes in the sky–can be derailed by countless forces, malevolent and well-intentioned alike. For decades, the environmental movement has oriented around stopping things, like coal power plants, oil refineries, and deforestation, from happening. Now, we have to pivot to getting things built, which entails a different mindset and demands compromise: we cannot power our economy with wind and solar without installing turbines and panels everywhere conceivable, sometimes in places that feature threatened species and pristine views.

At the same time, the barons of dirty, dying industries have leveraged the natural tendency to oppose local construction to launch so-called astroturf campaigns to stop renewable-energy development, bans on gas hookups, etc. As an example, late last year, a 400-megawatt solar project in Ohio was withdrawn due to local opposition, and Michael Thomas, writing in the great HEATED newsletter, recently told the story of Kevon Martis, an anti-renewables campaigner who “has helped pass dozens of laws that ban or severely restrict clean energy development in towns and counties across the Midwest.”

If that’s not bad enough, then consider the other barriers to electrification and decarbonization: bureaucracy, outdated permitting processes, bad customer service, and supply chain crunches all threaten the green transition. Here, I can speak from personal experience, as Capital Good Fund has seen several issues impede / delay our ability to install and operate a 24-kilowatt rooftop solar array and a fast-charging EV station at our headquarters. I hope what we’ve seen gives insight into the problems and solutions.

Trying to Go Solar

One of my top priorities after Capital Good Fund purchased a building in Providence, RI was to install solar panels on our roof. If you know me, you know I’m obsessed with solar. Not only have I installed panels on every home I’ve ever owned and sold (a condo in Providence, a home in Dedham, MA, and my current home in Los Angeles); not only does my nonprofit offer solar loans; but I even have a tattoo of panels on my leg (photo below). It isn’t just that solar is now the cheapest form of energy almost everywhere in the world, nor that the technology is crucial to building a just and sustainable future: I find great beauty in the fact that we have engineered a technology that is more efficient at converting sunlight into energy than plants, and that it does so with no moving parts and no emissions.

Unfortunately, going solar in America is way too difficult. I started by getting quotes from at least three installers, who somehow managed to send me three wildly different quotes: different in terms of cost-per-watt, maximum amount of panels that can fit on the roof, even what utility programs are available to nonprofits. Despite being fairly expert in the area, I had to spend hours sifting through the proposals and researching filings from the Public Utilities Commission to compare what I learned to what the installers told me. Homeowners are inundated with door-to-door salesmen hawking “free solar” and then offered financing with massive, hidden dealer fees (an issue I’ve written about twice). Needless to say, this is not conducive to increasing adoption of this magic, low-cost, emissions-free technology.

Unfortunately, going solar in America is way too difficult. I started by getting quotes from at least three installers, who somehow managed to send me three wildly different quotes: different in terms of cost-per-watt, maximum amount of panels that can fit on the roof, even what utility programs are available to nonprofits. Despite being fairly expert in the area, I had to spend hours sifting through the proposals and researching filings from the Public Utilities Commission to compare what I learned to what the installers told me. Homeowners are inundated with door-to-door salesmen hawking “free solar” and then offered financing with massive, hidden dealer fees (an issue I’ve written about twice). Needless to say, this is not conducive to increasing adoption of this magic, low-cost, emissions-free technology.

Yet that’s not the worst of it! Once we selected an installer–New England Clean Energy, which quoted us a 24-kilowatt system at just $2.77 per watt, a great price–we thought the panels would be on the roof and producing power within two months, maybe three. Instead, it took six months just to get the panels installed and for the City of Providence to complete the inspection. There were delays due to supply chain issues; the City requiring an engineering study of our roof which was obviously unnecessary; and coordinating the inspectors, the installers, and my staff to get it all done. Okay, we thought, now we just need the utility to provide Permission to Operate (PTO) and we’ll be all set–making energy and earning money! Nope. Between the time we started the project and were ready for PTO, National Grid, the local utility, had been sold Rhode Island Energy.

Whether because of the sale, incompetence, a desire to slow-walk distributed renewable projects, or all of the above, the utility came back and told the installer that they had to move the meter from inside the building to the street. This despite their having approved the initial designs and our installer providing ample documentation for why there’s no rationale for doing so. But Rhode Island Energy wouldn’t budge (though they did agree to cover the c0st). As you can imagine, this resulted in additional delays, including our installer having to source a meter socket (in short supply), coordinating with the utility, and scheduling a crew to come out. They are almost done with that work, at which point we’ll have to ask the utility to finally give PTO–and who knows how long that will take.

So to summarize. In June, 2021, we signed the agreement with the installer. In late December of that year, we finally got the permitting completed with the City. In April of 2022, the panels were finally installed. And here we are in February of 2023, over 1.5 years later, still not producing energy. Now to be clear, this is an outlier; I’ve never seen a project take this long. Nevertheless, it is unacceptable that we have made solar projects so complicated and time-consuming.

Fortunately, there are solutions. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has built a free, open-source tool called SolarAPP+, that reduces permitting costs by automating the process; alas, only 16 jurisdictions have adopted the tool. And a lot more can be done to simplify the interconnection process with utilities, protect consumers from unscrupulous practices, and raise awareness of solar through Solarize campaigns. What would the benefits be? According to Bloomberg, installers “could reduce their total costs by as much as 40%, including gross margins, if they could make the sale, installation and interconnection of the system in one to three days.” That’s the difference between solar being feasible and infeasible for millions of families. It would be an utter game-changer, and we can get there, if we try.

EV Charging

Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the U.S. There is widespread agreement that the best solution is electrification–battery-powered passenger vehicles, buses, and trucks, charged by an increasingly green electrical grid. Recognizing this, the federal government has set a goal for half of all vehicles sold by 2030 to be electric, which, according to McKinsey, will “require 1.2 million public EV chargers…by that year,” a twenty-fold increase compared to today. The good news is that Congress has allocated billions of dollars to incentivize a national charging network.

The bad news is that we can’t just install these chargers, hard as that is on its own. We have to make sure that they are equitably distributed, especially in underserved communities; that the stations work; and that the grid can handle the megawatts of power large charging stations require. Already, as the adoption of EVs surges, drivers are finding that stations are plagued by non-functioning chargers, gas vehicles blocking spaces, confusing pricing, confusing apps, and inconvenient locations. It would be like showing up at a gas station with a 25% chance that the pump doesn’t work. It’s unacceptable.

Capital Good Fund’s EV station

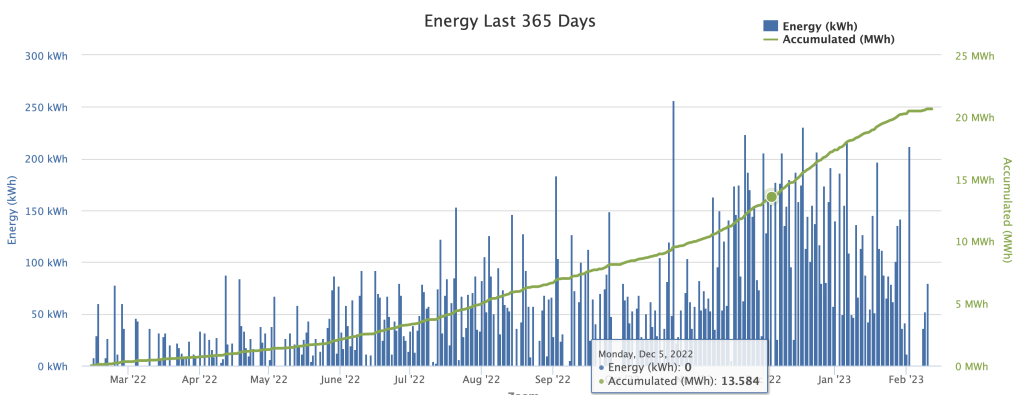

Given Capital Good Fund’s focus on an equitable green economy, we decided to install a level 3 fast-charging station in our lot. We saw it as an opportunity to increase access to charging in lower-income neighborhoods, as we are near the highway and the Rhode Island State House and in a residential area; to offer free charging to our employees as a way to incentivize switching to an EV; and to charge a rate that allows us to cover costs, if not generate a little bit of profit. The cost to install a high-end station, like the Chargepoint unit we purchased, is over $70,000. That price includes the station itself as well as the installation of a new meter and all of the wiring, trenching, and so on. We were fortunate that the utility and the state had a grant program; at the end of the day, we only had to pay $13,000 out-of-pocket. Even better, the installation process was reasonably efficient! And up until a week ago, usage was on the upswing. Below is a chart showing how much electricity we have dispensed each month for the last year:

See how the numbers go way down in February of this year? That’s because, unbeknownst to me, the station operator, the coolant level had dropped and caused a coolant pump to fail. I only found out about it 3 days after the station stopped working because one of my employees told me that the station read Unavailable on the physical unit (the back-end sent me no notification). I called Chargepoint, the manufacturer, who told me that, oops, they had sent a technician out for routine maintenance last December, he had noticed that the coolant was low, but forgot to put in a work order to have it topped off. I spoke to them on Tuesday, and as of this writing (Sunday), I’m still waiting to hear when someone will come out to carry out the repairs. (For some reason, drivers can use the station, even though the app says it’s out of service; I can only hope that they’re not damaging it even further in so doing.)

By the time the station is repaired, it will have been down, or semi-down I guess, for two weeks. Again, imagine a highly used gas station that drivers rely on not working for this long! And keep in mind that we have a top-of-the-line unit with a (supposedly) great warranty and service plan; I don’t want to think about what happens with lower-quality stations and companies.

The Governor of RI celebrating our station; the State wants to increase adoption of EVs

Summary

Look, it’s still relatively early days, especially in the mass adoption of EVs. We will sort many of these issues out, through policy, incentives, and market competition. That said, we cannot ignore the challenges. It’s not hard to envision a scenario in which word gets around that EV drivers are finding it impractical to use their cars because of broken chargers, or that homeowners are fed up with the complexity, cost, and lack of transparency in the solar industry.

This is a pivotal moment. The regulatory landscape is shifting, the technology is ready and affordable, and consumers and businesses are eager to adopt it. If we don’t get this right, we put in jeopardy the rapid and just green transition that is essential to preventing the worst impacts of climate change. Fossil fuel companies, utilities, and their ilk are rooting for us to fail. The future is in our hands.

Leave A Reply